There is nothing more frustrating and costly in the bindery than finishing up a beautiful job and having it rejected due to transit damage. This type of damage refers to those scratches, smudges, tears, offset pages, bent corners, dented edges or soiled product that happens during shipping. There are two popular misconceptions about packaging printed materials which when understood, will help you avoid costly damage to high-value printed material.

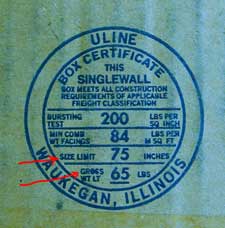

The first mistaken belief has to do with that little circle or square on the bottom of corrugated boxes known as the Box Manufacturer's Certificates (BMC.) It guarantees that the National Motor Freight Classification Standards (NMFC) construction requirements have been met in the making of the corrugated.

The first mistaken belief has to do with that little circle or square on the bottom of corrugated boxes known as the Box Manufacturer's Certificates (BMC.) It guarantees that the National Motor Freight Classification Standards (NMFC) construction requirements have been met in the making of the corrugated.

Looking at the certificate shown, if your box is within size limits (length + girth) and the gross weight of box plus contents is within limits, you probably would think it safe to ship. The reality is that if it’s anywhere near those limits and you ship it via any popular parcel service, it’s almost certain that the box and or contents will be damaged.

The purpose of the BMC is to protect the carrier and insurance companies, not necessarily to guarantee protection of your products. According to the International Safe Transit Association (ISTA) they are used by freight carriers and their insurance companies as an “enforcement tool in assessing damage claims”.

If a damaged box lacks a BMC, there is no liability for damage. If it has a BMC which meets the National Motor Freight Classification Standards known as “Item 222” then it will continue with a claims process. This requirement simply means the size and weight are within limits for the strength of corrugated used and that the BMC actually appears on all boxes. If it doesn’t meet this standard, a claim could be denied. These days it would be hard to find an off-the-shelf box without this certification.

The problem with this standard is that it is not a specification to help you select a box for single-parcel shipment. The NMFC standards are really designed for cartons which are to be palletized, strapped and wrapped. These trucking standards date back to railroad days when corrugated was first introduced to replace the wooden crates required in rail shipping. In reality they are of little use in predicting how a box will fare shipping via Fedex, UPS or the USPS parcel services. In fact the Institute of Packaging Professionals (iopp.org) recommends limiting the shipping weight to 50% of the allowable weight listed on the BMC.

You may not know this, but Fedex and UPS each have their own packaging standards regarding printed material. According to UPS packing guidelines, "Maximum size limit specified on the Box Maker's Certificate and the box strength guidelines chart is NOT the same as the UPS combined length and girth measurement." Their suggested packing might surprise you if you haven’t done much single-parcel shipping.

Fedex, for instance, recommends that printed matter be shipped in double-wall, full overlap or telescopic corrugated boxes at weights much lighter than the certifications might lead you to believe. Single-wall corrugated, gift boxes, banker boxes or bulk paper supply boxes are not recommended.

UPS has similar recommendations on their UPS Packaging Advisor page. Having been the recipient of numerous boxes of printed materials, shipped in single-wall corrugated and weighing 50-70 lbs, I can attest to the fact that their recommendations have a lot of merit! The only boxes we’ve ever received in that category without damage were all double boxed.

The second misconception about packaging and shipping printed material is that most of us think of printed sheets as rather solid. A stack of flat sheets, neatly jogged and packed in a tight-fitting box seems very solid, does it not? According to one study at the ISTA, it is not. Paper stacked in a box is a “flowable solid” in much the same way that a box full of nuts and bolts would be. If a stack of paper is jostled within a box, it can exert an outward pressure on the wall of the box. As soon as that wall is bowed outward, it loses significant strength and is prone to failure.

One major finding according to the study is that "packages that were designed with corrugated board specifications in [MNFC Item 222]...did not provide protection to flowable contents for the single parcel shipments. The failure ranged from tape failure, tears and edges, to container 'blow-out.'” The tests in this study used two items: sheets of flat, stacked paper and nuts and bolts. Contrary to what you might think, package damage was similar for each. Take a 50# single wall corrugated box of nuts and bolts and drop it 3’ or so. It will probably break and spill everywhere. A box of paper will do the same thing.

A package going through any of the popular parcel systems is subject to repeated drops from significant heights, as well as to compression from stacking, to mechanical damage, vibration, humidity and temperature changes. The opportunity for damage is high. The tests in this study used both single and double-wall corrugated with burst strengths up to 350psi and all of them failed during real-world shipping.

Although the study is from 2001, it’s still relevant today, judging by the scant attention paid by so many companies to the importance of shipping. Self-imposed standards by box manufacturers and single-parcel carriers have changed since the study but the shipping practices of many of their customers have not.

So is it hopeless? No. There are a few simple preventive measures you can take to avoid damaging printed material during shipping without breaking the bank.

- Use shrink wrap, strapping, paper banding or stationery boxes to pack and restrain the printed material within the shipping box. This prevents the ‘flow’ problem and maintains the integrity of the shipping box.

- Use smaller boxes and stay within the generally recommended limit of 50% of the maximum weight listed on the BMC.

- Use stronger corrugated and/or double-wall corrugated. Yes it’s more expensive but a few bucks more to ship a carton or two of an expensive job could easily prevent a far more costly re-print.

- Fill all voids within the box so there is no internal movement. (Here’s a related Bindery Success article on How to Pack a Box.)

- Seal all the seams on the box with a strong packaging tape.

- Change the orientation of the material within the box or use a different box to get a different, more effective orientation.

- Use only new corrugated boxes. Boxes weaken substantially when used only once. They also weaken with age. A box that’s been sitting in the warehouse for years will have just a fraction of the strength of a new one.

- Pack a box within a box. Both UPS and Fedex highlight this as the safest way to ship individual parcels.

- Test. If, for example, you’re doing an extensive drop shipment for your customer it’s a good idea to send some test packages first. Never shy away from testing. It’s the only way to find out how the package will truly fare.

Although it’s hard to protect against all possible damage, a little research, common sense and good practices will significantly increase the probability that your next valuable printed job will survive the grueling trip to your customer. Feel free to share your shipping experiences and wisdom below!