One of the best and most expensive lessons I ever learned was taught to me by an unprofitable saddle stitching job. I was reminded of it, and of the unchanging nature of humans, as I read a short article in a printing trade publication. It was written exactly one hundred years ago in 1914 yet it’s still timely. First the article, and then the story of a good idea gone bad.

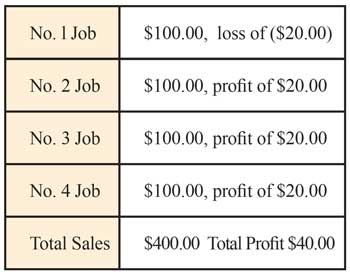

“The unprofitable job is at least twice as important as the profitable job. It will pay you well to ponder that deeply. Suppose a man gets four jobs of $100 each, and on one he loses $20, and on each of the other three turns a profit of $20. He might conclude that it is only one in four and does not matter much. He tries to forget it as soon as possible. However, in results it figures out as follows (table at right):

“The unprofitable job is at least twice as important as the profitable job. It will pay you well to ponder that deeply. Suppose a man gets four jobs of $100 each, and on one he loses $20, and on each of the other three turns a profit of $20. He might conclude that it is only one in four and does not matter much. He tries to forget it as soon as possible. However, in results it figures out as follows (table at right):

He has done $400 worth of business with a profit of $40, or 10 per cent. Suppose he cuts out the losing job; he would have done $300 worth of business, have a profit of $60, or 20 per cent--a DOUBLING of his percentage of profit.

But suppose a cost system helped him to get job No. 1 at a profit also, he would have $400 worth of business, a profit of $80, or 20 per cent. Attend to that unprofitable job and double your profit.

In this connection it might be well also to inquire closely concerning new work that seems to come your way. It may be someone else's “’most important job.’”

Of course the story is a simplification, yet it illustrates a truth about profit in business. Small changes in costs and production methods can change your overall profitability by a big margin. This is especially true if you can turn the losers—the most important job—into winners.

I had a taste of someone else’s “most important job” many years ago while running a small trade bindery. The caller, from a large web printing company, asked if I could do 500,000 stitched books to help them meet a deadline. It all sounded fantastic on paper and maybe even too good to be true, especially for me, a starving sole proprietor. Nevertheless, from the details I was given, the job should have been a piece of cake.

When the first tractor trailer load of signatures arrived, I immediately saw why they pawned the job off on me. In short, it was un-runnable. The signatures were curled every which way. The folding was as bad and inconsistent as you can imagine. The lip I needed to run the signatures came and went with each handful. It was the bindery job from hell.

When the first tractor trailer load of signatures arrived, I immediately saw why they pawned the job off on me. In short, it was un-runnable. The signatures were curled every which way. The folding was as bad and inconsistent as you can imagine. The lip I needed to run the signatures came and went with each handful. It was the bindery job from hell.

I tried to return the job but they volunteered to send their mechanic to update my stitcher to run with vacuum. Not trusting my gut, I gave in to their request. After the upgrade, the only way I could get it to run, and poorly at that, was to have someone at each pocket hand-curling every miserable stack of signatures. The customer agreed, verbally, to pay for the additional labor. I agreed to continue running, thinking that at least I’d break even, and perhaps have a chance at some more of their overflow work and possibly some profit.

As you might have already guessed, they never paid for the several weeks’ worth of extra labor. But I don’t blame them even though they broke a promise. It isn’t possible to turn every money-losing job into a winner, not without renegotiating the terms of the deal. In hindsight, their verbal OK to change the deal should have been in writing. But if I trusted my gut to refuse it right from the start, I would have avoided the financial beating and the headache altogether.

In my experience there has always been a tendency to discount the importance of profitability in post-press and bindery work. This is more the case in larger commercial print shops that have a bindery operation, rather than in a trade bindery whose reason for being is bindery work. The idea for printers seems to be that “as long as I make money on the print job as a whole, I’m OK with break-even or losses in the bindery.”

As our 1914 writer says, you better “ponder that deeply.” A very small improvement in the bindery can have a disproportionately positive effect on profitability as a whole. Considering the complexity and number of variables involved in bindery work, the opportunities for profit enhancement are almost endless.

Have a story about your own “most important job?” Feel free to share below!